Concurrent Algorithms

41min

October 18, 2023

These are my lecture notes and comments for the Concurrent Computing course at EPFL. The reference for these notes are prof. Rachid Guerraoui’s lectures and his book Algorithms for Concurrent Systems. I have tried to reformulate some proofs in order to better understand the subject. This post deals with more advanced topics than locking, it’s main concern is to implement wait-free concurrent algorithms.

Assumptions

Process

Processes model a sequential program, which means that, after invoking an operation op1 on some object O1, a process does not invoke a new operation (on the same or on some other object) until it receives the reply for op1.. In our model we assume that there are N processes which are unique and know each other. Additionally, a process either executes the algorithm assigned to it or crashes without ever recovering.

A process that doesn’t crash in a given execution is considered correct.n (on the same or on some other object) until it receives the reply for op1.

Safety

Safety properties stipulate that nothing bad should happen. A property that can be violated at some time point T and never be satisfied again is a safety property.

Example: not lying

Liveness

Liveness properties stipulate that something good should happen. At any time T there is some hope that the property can be satisfied at a later time T' >= T.

Example: saying anything

It is trivial to have one without the other, however, the hard part (i.e telling the truth) is satisfying both.

Wait Freedom

Any correct process that invokes an operation eventually gets a reply, no matter what happens to the other processes (very slow or crash)

Atomicity (Linearizability)

Every operation appears to execute at some indivisible point in time (called linearization point) between the invocation and reply time events.

Registers

Registers are simple object on which we can perform read() or write(value) operations.

Register Types

Based on value:

- Binary: containt 1 bit (0 or 1)

- Multi-valued: contain any value from an infinite set (bounded or unbounded)

Based on the number of concurrent processes:

- Single reader, single writer - SRSW

- Multiple readers, single writer - MRSW

- Multiple readers, multiple writers - MRMW

Based on concurrency guarantees:

- Safe

- Regular

- Atomic

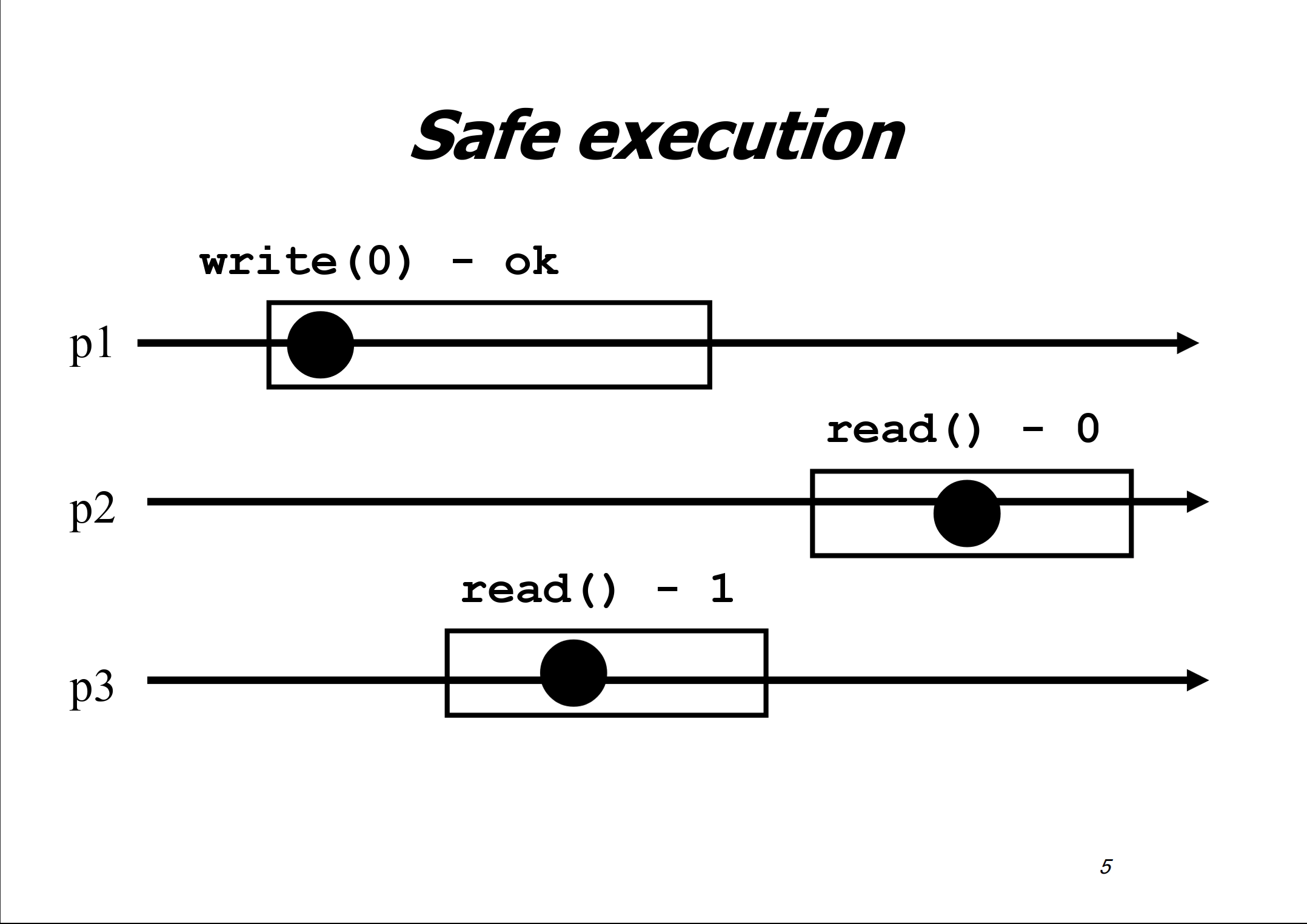

Safe register

Safety: A read that is not concurrent with a write returns the last written value. A safe register ensures safety. It only supports a single writer.

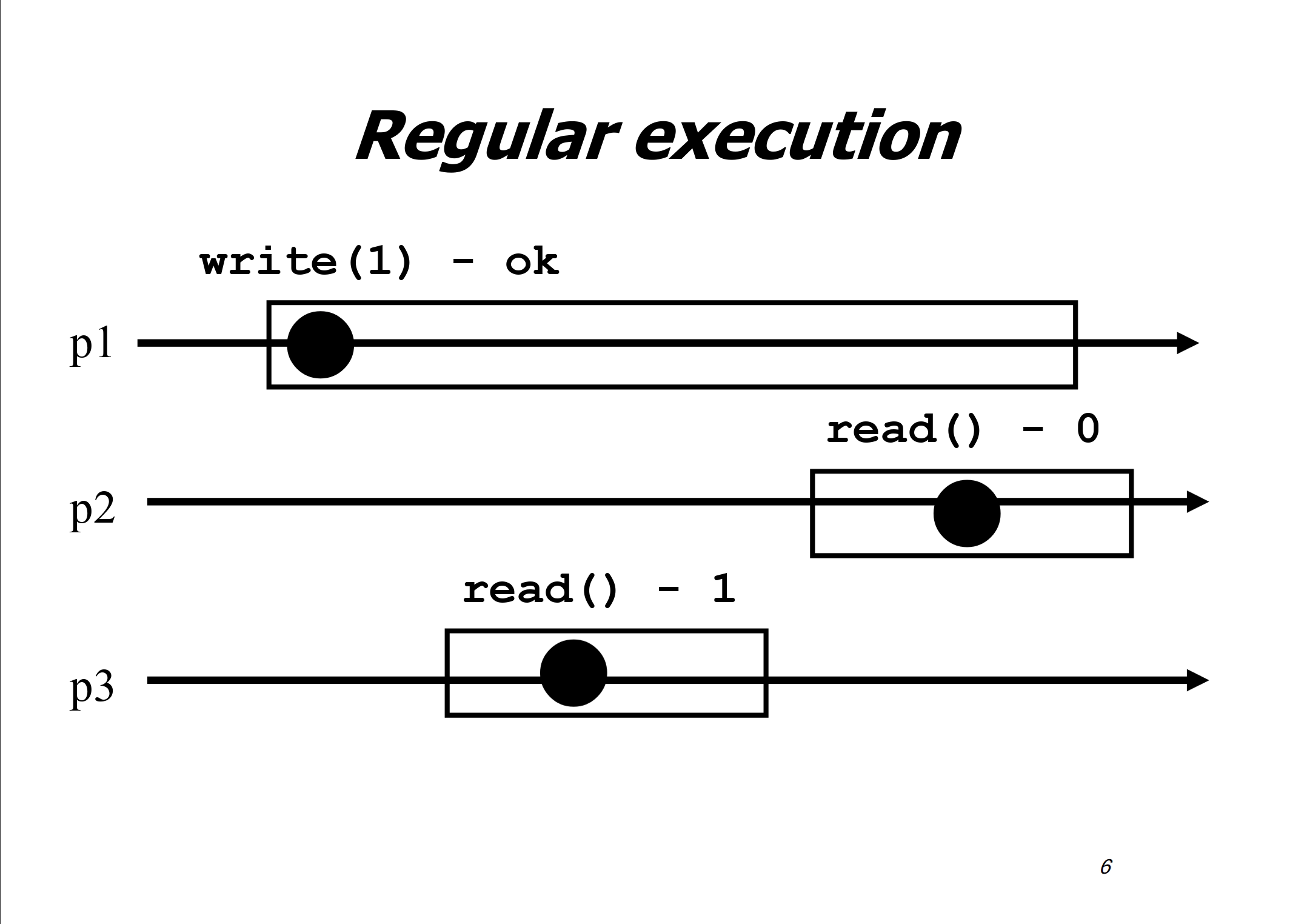

Regular register

Regularity: A read that is concurrent with a write returns the value written by that write or the value written by the last preceding write. A regular register ensures regularity and safety. It only supports a single writer.

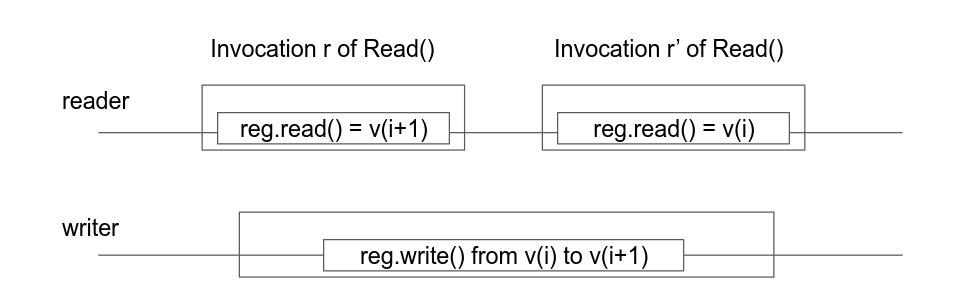

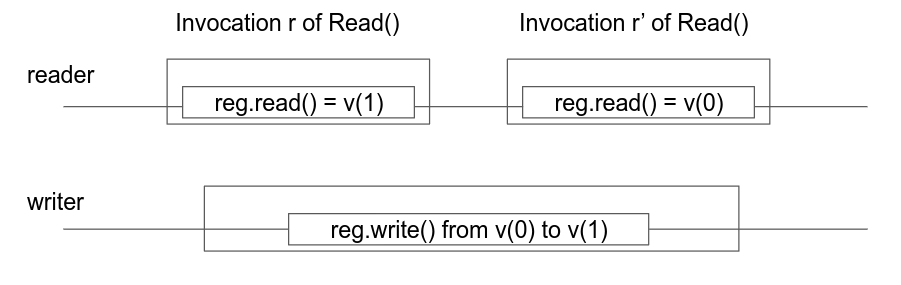

New-old inversion: when two consecutive (non-overlapping) reads are concurrent with a write, it is possible for a regular register to return the newely written value on the first read and the previously written value on the second read.

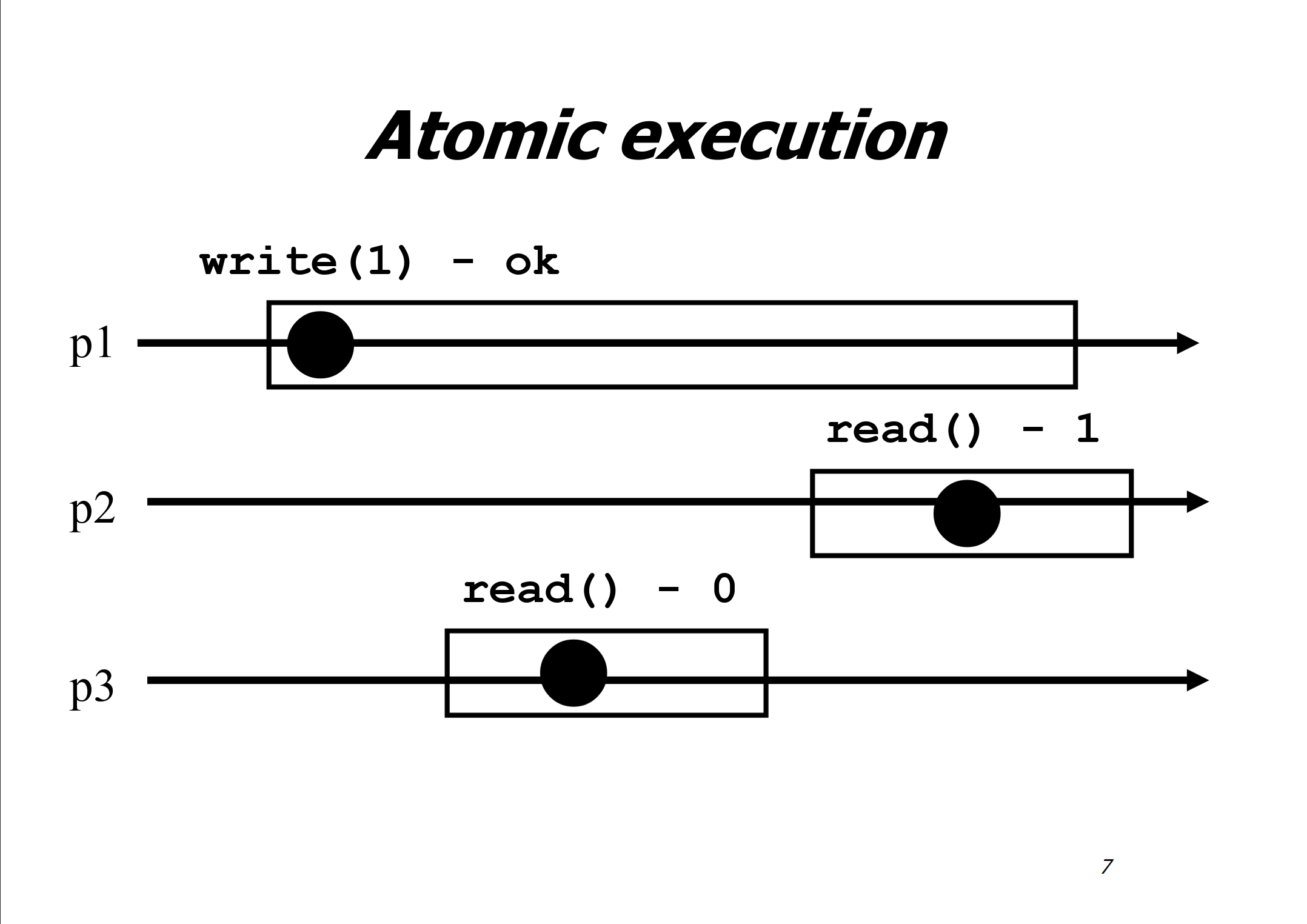

Atomic register

Atomicity: An atomic (linearizable) register is one that ensures linearizability. Such a register ensures the safety and regularity properties above, but in addition, prevents the situation of new-old inversion. The second read must succeed the first one in any linearization, and thus must return the same or a “newer” value.

Register Reductions

From (binary) SRSW safe register to (binary) MRSW safe register

We use an array of SRSW registers Reg[1…N], one per reader process.

| |

Proof Assume first that base 1W1R registers are safe. It follows directly from the algorithm that a read of R (i.e., R. read() ) that is not concurrent with a R. write() operation returns the last value deposited in the register R. The obtained register R is consequently safe while being 1WMR.

Let us now suppose that the base registers are regular. We will argue that the high-level register R constructed by the algorithm is a 1WMR regular one. Since a regular register is safe, the argument above implies that R is safe.

Hence, we only need to show that a read operation R. read() that is concurrent with one or more write operations returns a concurrently written value or the last written value. Let pi be any process that reads some value from R. When pi reads the base regular register REG[i] pi returns (a) the value of a concurrent write on REG[i] (if any) or (b) the last value written to REG[i] before such concurrent write operations. If the concurrent write R.write(v) managed to call Reg[i].write(v), then the concurrent read Reg[i].read() will return either the new value or the last written value. Otherwise, if the Reg[i].read() and Reg[i].write(v) aren’t concurrent, due to the safety property, the Reg[i].read() will return the last written value. Therefore the register is regular.

- Works for building MRSW safe register from SRSW safe register.

- Works for building MRSW regular register from SRSW regular register.

- Does not work for atomic register.

From binary MRSW safe to binary MRSW regular

We use one MRSW safe register

| |

Since the underlying base register is safe, a read that is not concurrent with any write returns the last written value.

Now consider a read operation r that overlaps with one or more write operations. If none of these operations change the value of the register, i.e. write to the underlying base safe register Reg, we are back to the previous case, as the read of Reg performed by r does not overlap with any write on Reg.

Now suppose that a concurrent operation changes the value of Reg. Thus, the value written by the last write that precedes r is different from the value written by the concurrent write. But the range of these values is {0, 1}. Since the read on the underlying base register returns a value in the range to any read, any of these values are accepted by the regularity conditions. Therefore the high-level register is regular.

- Works for single reader registers

- Doesn’t work for multi-valued registers

- Doesn’t work for atomic registers

From binary to M-valued MRSW regular

We use an array of MRSW Registers Reg[0 … M] initialized to [1,0,…,0].

- The value

vis represented by0s in registers1tov - 1and then1in register at positionv.

| |

Proof A R. write(v) operation trivially terminates in a finite number of its own steps: the for loop only goes through v iteration.

To see that a R. read() operation terminates in at most v iterations of the while loop, observe that whenever the writer changes sets REG[x] from 1 to 0, it has previously set to 1 another entry REG[y] such hat x < y ≤ b. Therefore, if a reader reads REG[x] and returns the new value 0, then a higher entry of the array is set to 1. As the running index of the while loop starts at 1 and is incremented each time the loop body is executed, it follows that the loop always terminates, and the value j it returns is such that 1 ≤ j ≤ b.

Proof Consider first a read operation that is not concurrent with any write, and let v be the last written value. By the write algorithm, when the corresponding R. write(v) terminates, the first entry of the array that equals 1 is REG[v] (i.e., REG[x] = 0 for 1 ≤ x ≤ v − 1). Because a read traverses the array starting from REG[1], then REG[2], etc., it necessarily reads until REG[v] and returns the value v.

Let us now consider a read operation R. read() that is concurrent with one or more write operations R. write(v1), . . ., R. write(vm) (as depicted in Figure 4.7). Let v0 be the value written by the last write operation that terminated before the operation R. read() starts. For simplicity we assume that each execution begins with a write operation that sets the value of R to an initial value. As a read operation always terminates (Lemma 2), the number of writes concurrent with the R. read() operation is finite. By the algorithm, the read operation finds 0 in REG[1] up to REG[v −1], 1 in REG[v], and then returns v. We are going to show by induction that each of these base-object reads returns a value previously or concurrently written by a write operation in R. write(v0), R. write(v1), . . ., R. write(vm). Since R. write(v0) sets REG[v0] to 1 and REG[v0 − 1] down to REG[1] to 0, the first base-object read performed by the R. read() operation returns the value written by R. write(v0) or a concurrent write. Now suppose that the read on REG[j], for some j = 1, . . . , v − 1, returned 0 written by the latest preceding or a concurrent write operation R. write(vk) (k = 1, . . . , m). Notice that vk > j: otherwise, R. write(vk) would not touch REG[j]. By the algorithm, R. write(vk) has previously set REG[vk] to 1 and REG[vk − 1] down to REG[j + 1] to 0. Thus, since the base registers are regular, the subsequent read of REG[j + 1] performed within the R. read() operation can only return the value written by R. write(vk) or a subsequent write operation that is concurrent with R. read(). By induction, we derive that the read of REG[v] performed within R. read() returns a value written by the latest preceding or a concurrent write.

- Doesn’t work for atomic registers.

Consider that the register had a value

10, and then the writer did 2 writesw(1)and thenw(9). The first readr1is concurrent with both writes, it missed the first1(Reg[1] = 0) so it continues to read, but very slowly. Thenw(1)completes and the second writew(9)starts and writes a1atReg[9]and starts clearing, but again very slowly. The readr1now manages to find the1atReg[9]and then returns9. The readr2starts now and finds a1atReg[1]fromw(1)and returns1. This is new-old inversion.

From SRSW regular to SRSW atomic

For this, we need an “unbounded” sequence number. This is not very realistic, however, there are techniques to recycle the timestamps of bounded sequence numbers, so that they appear unbounded.

Generally, each register will contain, along the data, a sequence number or a timestamp.

| |

Safety: trivial.

By memorizing the last_timestamp and last_value in the reader, we can prevent a new-old inversion, as the first read will update the last_timestamp and last_value, therefore, when the second read happens, it will read a lower timestamp and will just return the last_value.

Doesn’t work for multiple readers, because the second reader doesn’t have the updated last_timestamp and last_value, therefore, a new-old inversion could still happen.

From SRSW atomic to MRSW atomic

If we tried the simple transformation with N SRSW atomic registers, one for each reader:

| |

This will not be atomic. Consider 3 processes, pw - writer process, p1 - reader process and p10 - reader process. The writer starts writing a value x to the register and overwrites the Reg[1]. Concurrent to the write, p1 reads and returns the new value x, but the writer still hasn’t managed to overwrite the Reg[10], so when the p10 reads, it will return the old value. This unfortunately violates atomicity as Reg[10] would have to return the new value x as well.

In order to make this atomic, we will need to have communication between each two readers, by using the atomic SRSW registers. Thus, we would need N^2 registers. In ReadReg[i][j], the reader is pi and the writer is pj.

| |

It would not work for multiple writers, as they compute timestamp locally. For example, let’s say that writer p1 wrote 5 times, eat means it’s current timestamp is 5. Now, let’s say that p2 wrote, it’s timestamp would now be 1. How would the reader now which timestamp is correct? If it returns the maximum timestamp it would incorrectly return old value (violates safety).

From MRSW atomic to MRMW atomic

Following the intuition from the previous example, we need to have communication between the writers as well.

We use N MRSW atomic registers, the writer of Reg[i] is pi.

| |

We need to choose the maximum (or minimum) such k, so that two concurrent write operations don’t choose the same sequence number. For example, assume we have two processes which write, p1 and p2. They write concurrently the values 1 and 2 respectively. Because the neither one completes the write operation before the other one reads, the resulting registers look like this: Reg = [(timestamp: 1, value: 1), (timestamp: 1, value: 2)]. Now, we have 2 reads which happen sequentially one after another. If we don’t impose the ordering, the first read could read the value 1, the second value 2. This would violate safety, as the reads which are not concurrent with a write would have to return the last written value (which should be the same).

With the ordering, it is atomic, because the only case when we can possibly return different values on reads are when maximum timestamp is not unique. However, the ordering property will always force us to pick the same timestamp in this situation, thus we will always return the same value. Therefore, a new-old inversion is not possible.

Safety and regularity are trivially satisfied.

Impossibility Results

In this chapter we will prove some impossibility results and complexity lower bounds for making atomic registers from base safe registers.

Bound on SRSW atomic register implementations

There is no wait-free algorithm that:

- Implements a SRSW atomic register

- Uses a finite number of bound SRSW regular registers

- Where the base registers can only be written by the writer

Without loss of generality, we can assume:

- The higher-level register is binary

- Instead of finitely many SRSW regular registers, there is only one SRSW regular register (called reg) - say we had N registers, then the big register will hold N bits, each representing one register.

Adverserial example:

Writer alternates between writing 0 and 1 on the atomic register infinite times.

The implementing algorithm uses finite number of registers - M, each holding 0 or 1, which means there are 2^M different values. Say that in the given sequence, each different value written to the underlying register is written at most X times, that means that there are 2^M* X writes, which is not possible since there are infinite number of writes. Hence, when a Write(0) occurs, there has to be a value v0 which occurs an infinite amount of times. Similarly, there has to be a value vn which occurs an infinite amount of times when doing a Write(1) operation.

Let’s say that when writing a 1, the register goes through some kind of a sequence of values from v0 to vn. This sequence might not be the same every time, however, analogous to the previous argument, there will have to be some sequence of value changes from such that it repeats infinitely often (as otherwise we would have to have an infinite number of written values, but the registers are bounded) - let that sequence be v0, v1, … , vn.

Let’s say that we schedule a long write, and reads to happen inbetween underlying value writes vi and vi + 1 (after vi and before vi + 1). At some point, one of these writes has to cause the reader to read a 1, let the value written before such write be vi (it may happen multiple times, but at least once, otherwise, we would not be able to write anything into the register).

Now, we can schedule two consecutive reads - r1 and r2 to be concurrent to the write vi + 1. Because of the regular property of the underlying registers, both reads can return the previous written value vi or the current value vi + 1. Therefore, r1 can read vi + 1 and then r2 can read vi, causing a new-old inversion which breaks atomicity.

In case it was v1 causing the read to read a 1, then the r2 will read v0 as the previous value, while r1 can read v1.

In case it was v1 causing the read to read a 1, then the r2 will read v0 as the previous value, while r1 can read v1.

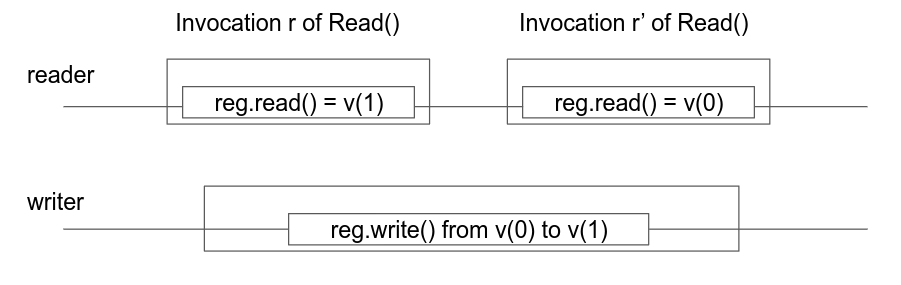

Bound on MRSW atomic register implementations

There is no wait-free algorithm that:

- Implements a MRSW atomic register,

- Uses any number of SRSW atomic registers,

- And where the base registers can only be written by the writer

Proof:

Let’s assume that this is true for 1 writer and 2 readers, because if it is, then it will be true for any greater number of multiple readers as well.

If the algorithm A uses an any number of SRSW atomic registers, then it is the same as having 1 register per reader, same proof as in the regular to atomic impossibility result.

We also assume that it is true for “binary” registers, therefore it would hold true for M-valued registers as well.

MRSW register atom initially has 0. Consider the atom.Write(1) operation.

w1, ..., wn are individual writes to the SRSW registers (one at a time). If the writer is communicating with reader r (i.e writing to his register), then the reader r' will not see this and will always return the same value, and vice-versa.

Because the readers have to read 0 before the write and 1 after the write. Therefore, there is some i, j, i != j for which ri = 0 and ri+1 = 1, and, r'j = 0 and r'j + 1 = 1, because w1, ..., wn are writes to separate registers (cannot communicate with both readers at the same time).

Let’s assume, without loss of generality that i < j. Then, if we schedule the reader r to read after i + 1, then it will have to return 1. Afterwards, we can schedule the reader r' to read, however, because the write was happening to the r’s register, then, for the reader r' it’s as if the write never happened, therefore, it would have to read the value that was before the write, which is r'i. Since, the reader’s return value changes at r'j+1, where j > i, therefore, the reader r' reads a 0 and we have a new-old inversion.

To conclude, readers must communicate in order to implement an MRSW atomic register from SRSW atomic registers.

The power of registers

In this chapter, we will discuss what is possible to implement just with registers and what isn’t.

Counter

A counter has two operations inc() and read() and maintains an integer x initialized to 0.

Naive implementation with just 1 register:

| |

However, this implementation is not correct, because 2 processes which call the inc() operation concurrently could both read 0 from the register and then write 1 to it, therefore, the result is 1 instead of 2.

To implement an atomic counter, the processes share an array of registers Reg[1 ... N]:

| |

With this implementation, even when we have concurrent inc() operations, the processes write to their own register, so it is not possible to have the processes read the same counter value while incrementing. When calling read(), it is not possible to have a new-old inversion, because this would mean that there exists a register k such that the first reader read the “newely” incremeneted value, while the second reader read the old value. This is not possible, as the register themselves are atomic.

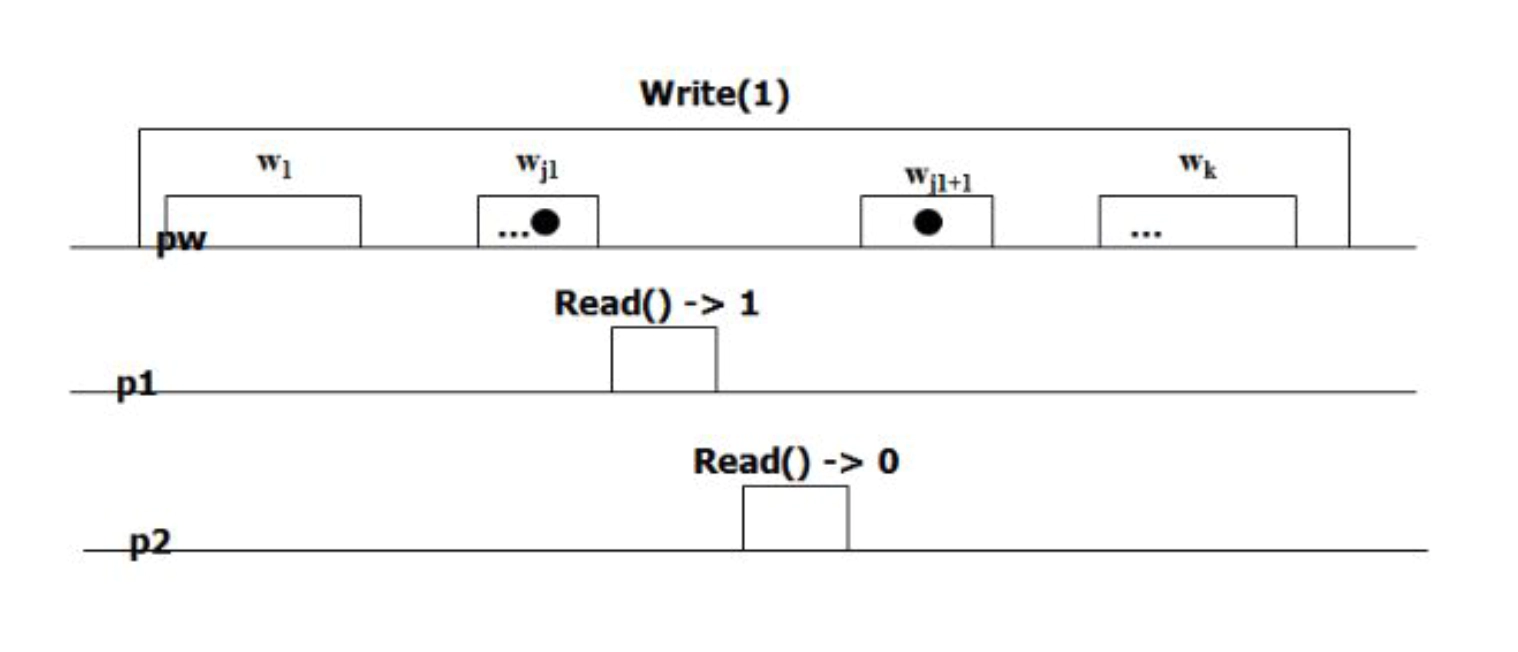

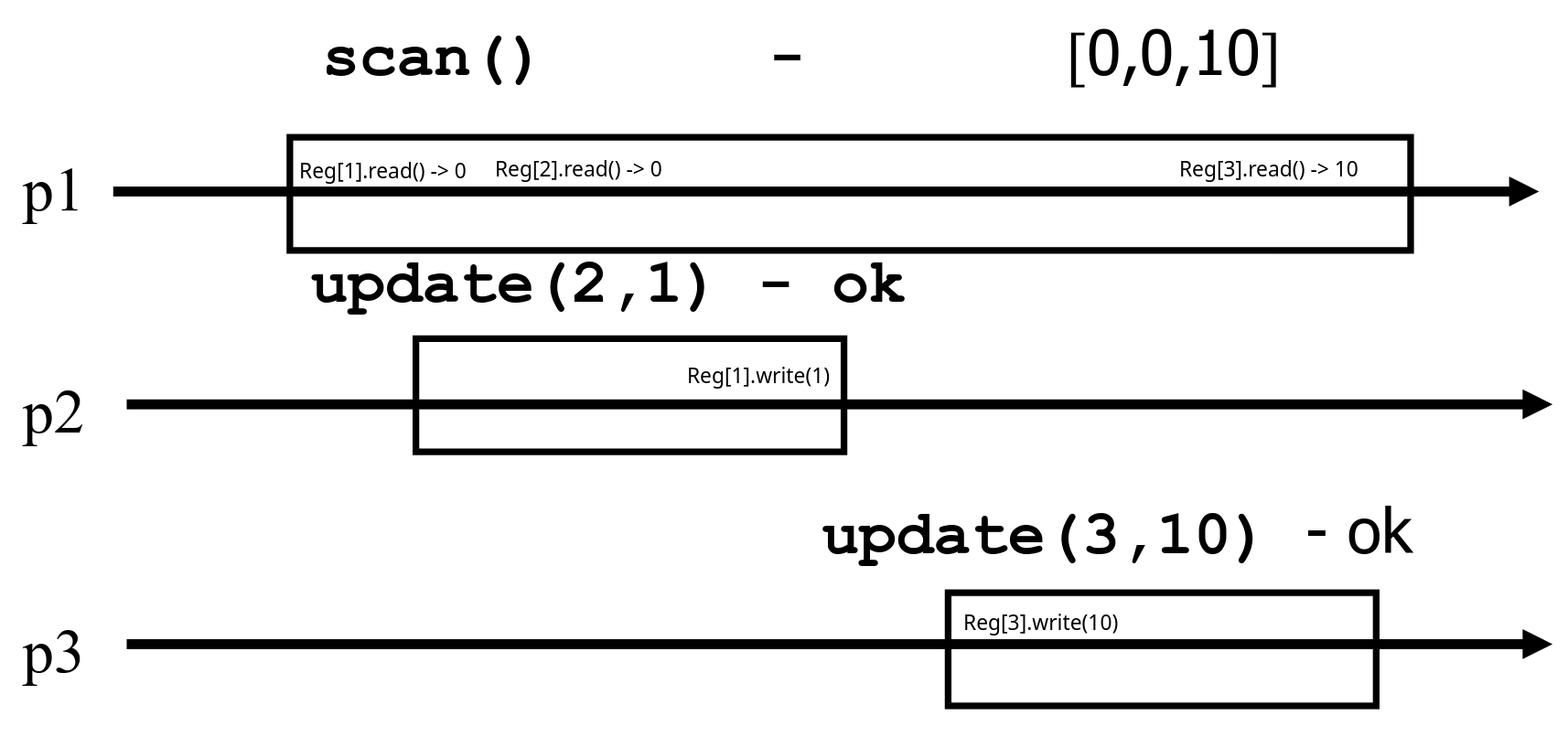

Snapshot

A snapshot has operations update() and scan() and maintains an array x of size N.

| |

Naive implementation - processes share one array of N atomic registers Reg[1 ... N]:

| |

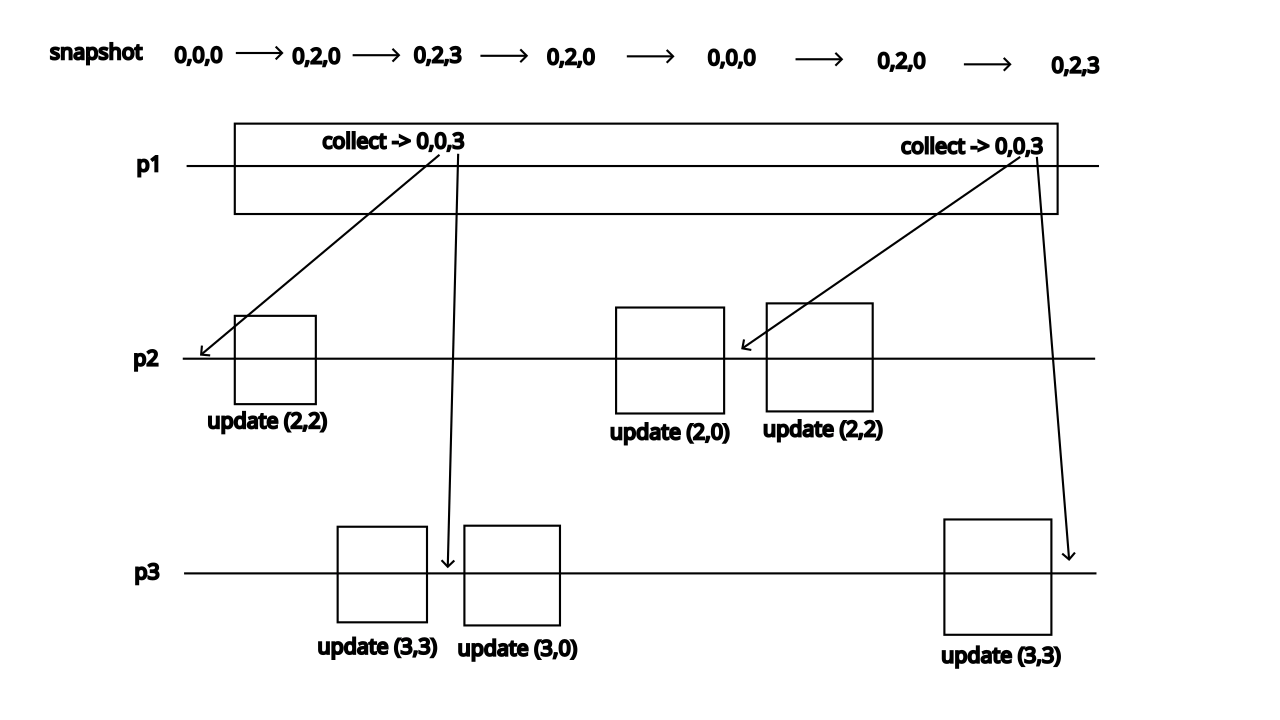

The problem with this implementation is that it is possible for a slow read to return an array which wasn’t “written” at any point in time.

In order to implement an atomic snapshot, we will first implement an operation collect, which returns, for every index of the snapshot, the last written values or the value of any concurrent update (the same as the scan operation in naive implementation).

Now, in order to successfully scan, the process keeps calling collect until two consecutive results are the same. This means that the snapshot did not change and it is safe to return without violating atomicity.

The processes share one array of N atomic registers Reg[1 ... N], each containing a value and a timestamp.

| |

Here, we need the timestamps, because if some writer updates the register to a new value, and then to an old one, the reader could collect the same values before and after the updates and terminate, not knowing that a write occured in between. This is problematic as given in the following example:

This implementation is atomic, however, it is not wait-free, because a process that reads could, in theory, never return if there are infinite concurrent writes.

To implement a wait-free snapshot, the processes share an array of registers Reg[1 ... N] that each contain:

- a value

- a timestamp

- a copy of the entire array of values

To scan, a process keeps collecting and returns a collect if it did not change, or some collect returned by a concurrent scan. Timetamps are used to check if the collect changes or if a scan has been taken in the meantime.

To update, a process calls scan and writes the value, the new timestamp and the result of the scan.

| |

Consensus

A consensus object makes a set of processes decide on a value. It has one operation: propose which returns a value. When a propose oepration returns, we say that the process decides. It has 3 properties:

- Aggreement: No two processes decide different values

- Validity: A decided value has to have been proposed by some process.

- Termination: Every correct process eventually decides a value.

LA (FLP) Impossibility

No asynchronous deterministic algorithm, implements consensus among two processes using only registers.

Proof: Consider two processes p0 and p1 and any number of registers, R1,…,Rk,… . Assume that a consensus algorithm A for p0 and p1 exists.

Initial configuration C is a set of (initial) values of p0 and p1 together with the values of the registers R1,…,Rk,… .

A step is an elementary action executed by some process pl: it consists in reading or writing a value in a register and changing pl’s state according to the algorithm A.

A schedule S is a sequence of steps; S(C) denotes the configurations that results from applying S to C. In an asynchronous environment, there are no constraints on the schedules (i.e any sequence of steps is a valid schedule).

A configuration C is 0-valent if, starting from C, no matter how the processes behave, no decision other than 0 is possible. Similarly for 1-valent configuration. If a configuration isn’t 1-valent or 0-valent, then it is bivalent.

Lemma 1: there is at least one initial bivalent configuration

Proof: The initial configuration C(0,1) is bivalent. If we start from configuration C(0,0) and then choose a schedule where p1 doesn’t take any steps until p0 decides (it must eventually decide because of the termination property of A), then p0 must decide 0. This is true if we apply the same schedule for the starting configuration C(0,1), since p0 cannot distinguish the configuration C(0,1) from C(0,0) if p1 is never scheduled. Similarly, if we start with the configuration C(1,1) and never schedule p0, then p1 must eventually decide 1. This is again true for the configuration C(0,1), since p1 cannot distinguish it from the configuration C(1,1) if p0 is never scheduled. Therefore, configuration C(0,1) is bivalent.

Lemma 2: Given any bivalent configuration C, there is an arbitarily long schedule S such that S(C) is bivalent.

Proof: Let S be the schedule with the maximum length such as D = S(C) is bivalent. p0(D) and p1(D) are both univalent: one of them is 0-valent (say p0(D)) and the other is 1-valent (say p1(D)). To go from D to p0(D), p0 accesses a register R which must be the same in both cases, otherwise p1(p0(D)) is the same as p0(p1(D)), because they access diferent registers, hence the order doesn’t matter. This is in contradiction with the very fact that p0(D) is 0-valent whereas p1(D) is 1-valent.

To go from D to p0(D), p0 cannot read R, otherwise R has the same state in D and in p0(D). In this case, the registers and p1 have the same state in p1(p0(D)) and p1(D) (because p0 just reads R and doesn’t write to it to communicate to p1). If p1 is the only one executing steps, then p1 eventually decides 1 in both cases, which is a contradiction with the fact that p0(D) is 0-valent. Similarly, p1 cannot read R to go from D to p1(D).

Thus both p0 and p1 write in R to go from D to p0(D), however, in that case p0(p1(D)) = p0(D) (because they overwrite each other). If p0 is the only one executing steps, then p0 eventually decides 0, which is a contradiction to the 1-valency of p1(D). Analogous p1(p0(D)) = p0(D), which is also a contradiction.

By using lemmas 1 and 2, there exists a bivalent initial configuration C and an infinite schedule S such that, for any prefix S' of S, S'(C) is bivalent. In an infinite schedule S, at least one process executes an infinite number of steps and does not decide, which is a contradiction to the termination property of A.

The limitations of registers

After thoroughly learning about registers, here we’ll present (and prove) some object which cannot be implemented with registers.

Fetch and Increment

Operation fetch_and_increment increments the counter and returns the new value.

Sequential specification:

| |

To prove that fetch and increment cannot be implemented only by using registers, we will implement consensus by using fetch&inc and registers. Since consensus cannot be implemented by using only registeres, the same applies to fetch&inc, otherwise, we would be able to swap the fetch&inc object with the registers and algorithm that implement it, and then implement the consensus by only using registers.

This implementation of 2-consensus uses fetch&inc object FC and 2 registers.

| |

Queue

Again, we will implement consensus by using a queue and show that an atomic wait-free queue cannot be implemented by using only registers.

We wiil use two register and a queue which is initialized to {winner, loser}.

| |

Test and set

The test and set object sets it value to 1 and returns the old value.

| |

Locking with test and set:

| |

2-consensus uses two registers and a test&set object T.

| |

Compare and swap

The c&s object compares if it’s value is equal to the old value, and if it is sets the value to the new value. It return it’s value before the change.

| |

Locking with c&s:

| |

Unlike other mentioned objects, the compare and swap object can implement consensus with an infinite number of processes (fetch&inc, queue and test&set can implement consensus with only 2 processes).

The implementation uses only a compare and swap object CS initialized to winner (here winner is chosen as it is easier to explain the algorithm, however, usually a C&S object will be initialized to some “falsy”/“empty” value).

| |

Universal Constructions

A type T is universal if, together with registers, instances of T can be used to provide a wait-free linearizable implementation of any other type (with a sequential specification).

Such an implementation is called a universal construction.

Consensus

Theorem 1: Consensus is universal.

Corollary 1: Compare and swap is universal.

Corollary 2: Test and set is universal in a system of 2 processes (it has consensus number 2).

Corollary to FLP/LA: Register is not universal in a system of at least 2 processes.

First we will consider deterministic objects and then non-deterministic ones. An object is deterministic if the result and final state of any operation depend only on the initial state and the arguments of the operation.

We give an algorithm where every process has a copy of the object (inherent for wait-freedom) and where processes communicate through registers and consensus objects (linearizability).

The processes share a (possibly infinite) array of MRSW registers Lreq used to inform all processes about which requests need to be performed.

The processes also share a consensus list Lcons (also of infinite size) that is used to ensure that the processes agree on a total order to perform the requests on their local copies. We use an ordered list of consensus objects where each objects is uniquely identified by an integer. Every consensus objects is used to agree on a set of requests (the integer is associated to this set).

The algorithm combines the shared registers Lreq[i] and the consensus object list Lcons to ensure that:

- Every request invoked by a correct process is performed and a result is eventually returned (wait-free)

- Requests are executed in the same total order at all processes (i.e., there is a linearization point)

- This order reflects the real-time order (the linearization point is within the interval of the operation)

Every process also uses two local data structures:

- A list of requests that the process has performed (on its local copy):

lPerf - A list of requests that the process has to perform:

lInv

Every request is uniquely identified.

Every process pi executes three tasks:

- Whenever

pihas a new request,piadds it toLreq[i]. - Periodically,

piadds the new elements of everyLreq[j]intolInv. - While

(lInv - lPerf)is not empty,piperforms requests usingLcons.

Task 3

While lInv - lPerf is not empty:

piproposeslInv – lPerffor a new consensus inLcons(increasing the consensus integer)piperforms the requests decided (that are not inLperf) on the local copy- For every performed request:

pireturns the result if the request is inLreq[i]piputs the request inlPerf

Corectness

Lemma 1 (wait-free): Every correct process pi that invokes a request eventually returns from that invocation.

Proof: Assume by contradiction that pi

does not return from that invocation; pi puts the request into Lreq (Task 1). Eventually, every proposed lInv - lPerf contains this request (Task 2). Because of the termination property of consensus, eventually a consensus decision contains the request (Task 3). The result is then eventually returned (Task 3)

Lemma 2 (order): The processes execute the requests in the same total order.

Proof: Because processes perform operations on their local copies only when a consensus decides on a set of requests and they use the same order to perform the operations, therefore every process will execute the operations from consensus in the same order. Since the consensus objects have integers associated with them, the object will first perform operations from the consensus with a lower integer number. Thus a total order is established.

Lemma 3 (real-time): If a request req1 precedes in real-time a request req2, then req2 appears in the linearization after req1.

Proof: It directly follows from the algorithm that the result of req2 is based on the state of req1.

Non-deterministic objects

An object is non-deterministic if the result and final state of an operation might differ even with the same initial state and the same arguments.

Assume that a non-deterministic type T is defined by a relation δ that maps each state s and each request o to a set of pairs (s’,r), where s’ is a new state and r is the returned result after applying request o to an object of T in state s.

Define a function δ' as follows: For any s and o, δ'(s,o) ∈ δ(s,o). The type defined by δ' is deterministic.

Every execution of the resulting (deterministic) object will satisfy the specification of T.

Task 3 (Non-deterministic)

While lInv – lPerf is not empty:

piproduces the reply and new state (update) from request by performing:(reply,update):= object.exec(request)piproposes(request,reply,update)to a new consensus inLcons(increasing the consensus integer) producing(re,rep,up).piupdates the local copy:object.update(up).pireturns the result if the request is inLreq[i].piputs(req,rep,up)inlPerf.

With determinism, if the processes decide on a request, because they all have the same state before it, then they can perform the request and get the same state and response always. However, with non-deterministic algorithms, this is not possible as some objects may return different replies and different states when performing the operation from the request. In this case, instead of proposing a request, we first “speculatively” execute the operation to get one possible next state and reply. Then we propose this trio so that all processes can have the same decided state and return the decided reply.

Obstruction-free Consensus

Instead of the termination property, Obstruction-free consensus has the Obstruction-free-termination property:

- Agreement: no two processes decide differently

- Validity: Any value decided must have been proposed

- Obstruction-free-termination: If a correct process proposes and eventually executes alone, then the process eventually decides.

A note that just because the process is executing alone, doesn’t mean that it will decide the value it proposed. It may decide any value proposed by any process.

Implementation

Each process pi maintains a timestamp ts, initialized to i and incremented by N.

The processes share an array of register pairs Reg[1,...,N] where each element of the array contains two registers:

Reg[i].Tcontains a timestamp (init to0)Reg[i].Vcontains a pair(value, timestamp)(init to(null, 0))

The function highestTsp() returns the highest timestamp among all elements Reg[1,...,N].T.

The function highestTspValue() returns the value with the highest timestamp among all elements Reg[1,...,N].V.

| |

Because the processes first write a timestamp, then write the value and the timestamp, and then read the highest timestamp again, this means that between the pi’s write of the timestamp and the highestTsp() call nobody else has written a newer timestamp. Meaning that there isn’t a newer value somebody else might read from highestTspValue() therefore, a process pj which reads after pi will read pi’s value as the newest, will write it with a new timestamp and then decide on it as well. Analougously, anybody after that process will read the pj’s value, which is actually pi’s value.

Otherwise, if pi reads a different timestamp from highestTsp() call, that means that someone else wrote a new value, therefore, pi cannot decide, because the new value might be different from the value val which pi read.

The problem with this algorithm is that it doesn’t gurantee termination. There could be an execution which never terminates, because a process managed to write a “newer” timestamp before another process pi finishes reading highestTsp(). Therefore, pi might find a timestamp which is newer than it’s own, so it must make another attempt. Then, the same could happen to other processes.

Eventual Leader Election

One operation leader() which does not take any input parameter and returns a boolean. A process considers itself leader if the boolean

leader() is true.

If a correct process invokes leader(), then the invocation returns and eventually, some correct process is permanently the only leader.

For the leader() to be implemented, we must assume an eventually synchronous system. There is a time after which there is a lower and an

upper bound on the delay for a process to execute a local action, a read or a write in shared memory. The time after which the system becomes synchronous is called the global stabilization time (GST) and is unknown to the processes.

This model captures the practical observation that distributed systems are usually synchronous and sometimes asynchronous.

| |

Every process pi elects the process with the lowest id that pi considers as non-crashed. If pi elects pj then j < i.

A process pi that considers self as a leader keeps incrementing Reg[i]. In other words, it is signaling other processes that it is a leader and that it is running. Eventually, only the leader keeps incrementing Reg[i].

Every process periodically runs the elect() function to see if there is a new leader. Because the processes don’t know the upper bound for processing (but it will exist at some point), they have to run this function less frequently (by doubling the delay), so that the processes which are slow (but haven’t crashed) can increment their register if they are the leader. This means that at some point, delay will be high enough for the non-crashed process with the smallest id to update it’s register in time for the next check. When all the processes reach that delay, they will elect it as the leader. This process will elect itself, because every process with a smaller id must have crashed (because the delay is greater than the upper bound on the computation).

Lock-free Consensus

- Aggreement: No two processes decide differently.

- Validity: A decided value has to have been proposed by some process.

- Lock-free-termination: If a correct process proposes, then at least one correct process eventually decides.

The idea is to use an eventual leader to make sure that, eventually, one process keeps executing steps alone, until that process decides.

| |

Because there can be multiple leaders until eventual leader is elected, we still must rely on “optimistic locks” (the algorithm from obstruction-free consensus) to ensure that mutliple leaders don’t decide differently. Eventually, due to the synchrony assumptions and the eventual leader algorithm, there will be only 1 leader and 1 process which executes the algorithm, therefore, it will decide. This fixes the case of infinite execution in the obstruction-free consensus algorithm, because eventually, the leader will terminate.

However, the shortcoming of this algorithm is that when an eventual leader arises, unless it crashes, it will be the only process that decides, as it will be the only process running the algorithm. Therefore, other processes will not decide (this is why it isn’t wait-free as not every process terminates).

Wait-free consensus

To solve the problem of lock-free consensus, instead of deciding, the leader will write the decided value to a shared register Dec which everyone reads from. Once there’s a value in that register, it means that the processes can stop running the algorithm and decide as well. Very elegent and simple :)

| |

Computing with anonymous processes

In this model, it is assumed that the process don’t have identifiers and cannot identify other processes. This means that every process runs exactly the same code (in previous algorithms, while the algorithms of the processes were the same, each process had a different implementation that accounts for its identifier).

A system is called anonymous if processes are programmed identically.

In such systems it doesn’t make sense to use single writer registers, as the usage of single-writer registers would violate total anonymity by giving processes at least some rudimentary sense of identity: processes would know that values written into the same register at different times were produced by the same process.

Weak Counter

A weak count procides a single operation - wInc() which returns an integer. It has the property that if one operation precedes another, the value returned by the later operation must be larger than the value returned by the earlier one (Two concurrent wInc() operations may return the same value). Also, the return value does not exceed the number of wInc() invocations.

Sequential specification:

| |

This is essentially a weaker form of a fetch&increment object.

Lock-free implementation - The processes share an infinite array of MWMR registers Reg[1...n...], initialized to 0.

| |

This implementation is not wait-free, because a process can forever keep reading 0 from Reg[i] if there is contention. In order to alleviate this problem, the processes also use a MWMR register L. Whenever a process writes a 1 into an entry of Reg, it also writes the index of the entry into a shared register L (initialized to 0). A process may terminate early if it sees that n writes to L have occurred since its invocation. In this case, it returns the largest value it has seen in L.

| |

Wait-freedom proof: Suppose that some process p never returns from wInc(). This must mean that it is stuck in an infinite loop. This means that an infinite number of writes to L will occur. Suppose, some process q writes a value i into L. Before doing so, it must write 1 into Reg[i]. Thus, any subsequent invocation of wInc() by q will never see Reg[i] == 0. Therefore, q can never again write i to L (because it will always read 1 from L and continue to search for the next i such that Reg[i] = 0). Thus, p’s operation will eventually see n different values in L and terminate, contrary to the assumption.

Correctness: Let r1 and r2 be the values returned by op1 and op2, where op1 completes before op2. We must show that r2 > r1. If op1 terminates, then it must mean that Reg[r1] = 1 (either op1 wrote to it, or some other register wrote to it and wrote r1 to L and op1 terminated early). If op2 terminates after writing to Reg[r2] = 1, then it must meant that Reg[r2] = 0 at some point (in order to break the loop). If r2 <= r1, then when op1 read from Reg[r2] it must have read 1 (because the 1 to Reg are written sequentially), but this is a contradiction to Reg[r2] = 0. Therefore, in this case r2 > r1. If op2 terminated early, then it has seen the value in L change n times, so at least 1 process wrote to L twice during that time. This means that there is an op3 which started after op2 began and terminated after writing to Reg[r3] (the second operation of the process). Therefore, op3 started after op1 terminated, following the same argument, it must mean that r3 > r1. Because op2 returns the max value, then r2 >= r3 > r1.

Snapshot

Wait-free implementation: similar to the snapshot with process identifiers. The processes share a Weak Counter initialized to 0 and an array of registers Reg[1...N] that each contain:

- a value

- a timestamp

- a copy of the entire array of values

To scan, a process keeps collecting and returns a collect if it did not change, or some collect returned by a concurrent scan. Timestamps are used to check if a scan has been taken in the meantime.

To update, a process scans and writes the value, the new timestamp and the result of the scan.

| |

Consensus

We are solving binary consensus. The processes share two infinite arrays of registers: Reg[0][1...i...] and Reg[1][1...i...]. Every process hold and integer i initialized to 1. The main idea is: to impose a value v, a process needs to be fast enough to fill in registers Reg[v][i].

| |